Last Two Men to Die At Camp Chase

By Dennis Ranney, SCV and Joanie Jackson, UDC

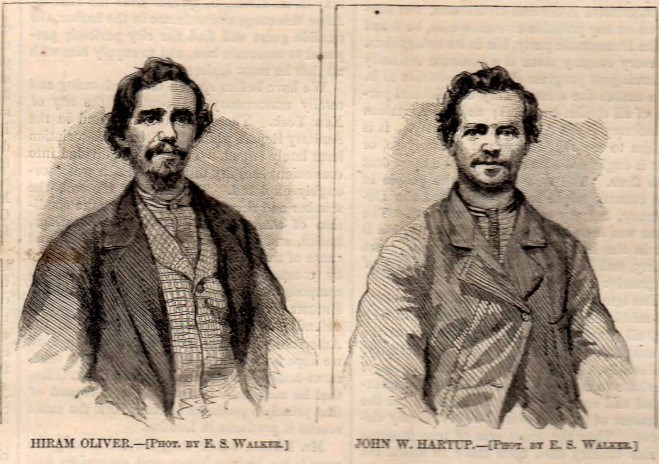

Ironically the only planned execution at the Camp Chase Prison was not Confederate but rather Union soldiers. Their military trial lasted for about two months in Cambridge, Ohio and was perhaps the most wide spread news event in Ohio during the 20th century. There are three (3) roles of micro-film just on the trial of Hartup and Oliver at the National Archives. It would probably take a week or so to read the whole transcripts of the trial.The newspaper article below mentions Hartup and Oliver and the compiler feels it necessary to explain who they were.

The two soldiers were brothers-in-law, this coming from a newspaper article from The Ohio Statesman and confirmed by census and marriage records. Given name spelled as Clarinda Hartup married Hiram Oliver on November 1, 1860 in Jefferson County, Ohio. The 1860 United States census had Clarinda Hartup born about 1836 and living in the household of John and Rachel Hartup and one family member was John W. Hartup, born about 1844. The family household was living in Jefferson County, Ohio and the census was enumerated in July 1860.

Hiram Oliver and John Wesley Hartup both served in Company A of the 43rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The 43rd Ohio Infantry had been formed at Camp Andrews located in Mount Vernon, Ohio on September 28, 1861 through February 1, 1862. The following was supplied by George Martin at The Civil War Message Board Portal. “Hiram Oliver residence was not listed; eighteen years old and enlisted on October 21, 1861 as a Private. On December 19, 1861 he mustered into Company A of the 43rd Infantry He was discharged for disability on July 28, 1862 at Camp Chase, Ohio.” Hiram Oliver of Company A of the 43rd Ohio Infantry filed for a pension on May 1, 1863 and his application number was 20849. It is currently not known when Hiram Oliver re-enlisted. “John W. Hartup residence was not listed; eighteen years old and enlisted on October 24, 1861 as a Private. On December 19, 1861 he was mustered into Company A of the 43rd Ohio Infantry.”

The compiler notes from prior research that Union deserters were not normally shot for their offense although a court martial was usually soon to follow. However if the deserter was shooting back at the arresting officer it might surely end badly for the deserter. Such was the case for Oliver and Hartup. Interestingly less than a week following the shooting and death of a Deputy Provost Marshal on March 5, 1865 at the hands of Oliver, President Lincoln had authorized an amnesty for Union deserters by a Presidential Proclamation number 124 to take effect on March 11, 1865. The Union deserters would have to report to a Provost Marshal within sixty days and then serve the period of time on active duty due to their period of desertion. The amnesty offer ended on May 10, 1865. View the proclamation here.

A Deputy Provost Marshal from Guernsey County, Ohio named John Beymer Cook was after Hartup and Oliver. Cook had a reputation of getting his deserters and tracking them down. Some newspaper articles stated Oliver and Hartup had been in deserter status since June of 1864 and in a few newspaper articles it was stated Cook had fired shots at one of them at Gibson’s Station (located in Guernsey County) Newspaper articles indicate that Oliver and Hartup had recently purchased adjoining farms in Clark County, Illinois. Fearing their pending arrest Oliver and Hartup devised a plan. On the evening of March 5, 1865 at Cambridge, Ohio Oliver knocked on the door of Deputy Provost Marshal Cook’s residence while Hartup stood nearby. When he answered Oliver asked to speak to Cook. When Cook replied who he was Oliver took his revolver out and shot him dead through his heart. When ask about the killing of Deputy Provost Marshal Cook, Oliver much later stated “Yes, I did it – Hartup did not. I did it because I thought that he [Cook] would come to Illinois and arrest me, as he had done and if he did I know that I would kill him or he would kill me. Yes, I am the guilty one. Oh my God, forgive me!” However, the Mrs. Cook was able to identify who had shot her husband and according to the newspaper, The Cleveland Daily Leader, on March 22, 1865 the boots of Oliver were very peculiar, having both heel and toe plates, which are very unusual and which make very distinct tracks. The two were arrested hiding in a barn in Londonberry, Ohio a few days later after the assassination of Cook. (Londonberry, Ohio today is an unincorporated town in Guernsey County)

The soldiers were hanged next to prison number 1 at the Camp Chase Prison on September 6, 1865. The newspaper The Ohio Statesman also stated Oliver kissed his wife and children good-bye and ask that they be given a religious upbringing. Oliver’s family came to the Guard House at Camp Chase to give their final good-byes. The newspaper The Ohio State Journal reported The solemn dead march, played by the band of the 22nd (Veteran Reserve Corps) the procession moved toward the scaffold. Scarcely was a start made when Mrs. Oliver, with heart rending shrieks, broke away from her attendants and rushed with her babe toward her husband, Kindly but firmly she was restrained and by those with tearful eyes taken to a more distant house and placed for the time under guard. Slowly the funeral procession of men yet living moved on to the last dread scene in the terrible drama.” “Several times came the firm, sorrowful order to go, but each time came such floods of bursting sorrow that the departure was delayed. A sturdy soldier took the little girl in his arms, an officer supported the half crazed mother to the door and Oliver was alone with his clergymen.” Oliver was dressed in black while Hartup was dressed in a checkered shirt vest and pants. On the platform a black cap was put over each of their heads. When the last Amen was heard the order was given to release the drop and Oliver and Hartup fell four feet. The neck of Oliver seemed broken by the fall and he scarcely struggled, but Hartup evidently died by strangulation and his struggles, were prolonged. It took more than twenty-six minutes before the body of Hartup was still. And then the paper stated if any of the relatives or friends wanted their bodies they could take them otherwise they would be buried at Camp Chase. After the execution, each man was placed in a red wooden coffin and the coffins were placed in a barracks at Camp Chase.

From the newspaper Ohio State Journal dated September 8, 1865. “Disposition of the bodies of Oliver and Hartup – After the execution, the bodies of Oliver and Hartup, the murderers of Provost Marshal Cook, were placed in coffins and left in the barracks at Camp Chase, to await the order of relatives. Yesterday morning Mrs. Oliver took possession of the remains and had them conveyed to the depot, in this city, intending to take them home for interment, but for want of sufficient means to pay express charges, was compelled to return with them to Camp Chase, where they were buried in separate graves in the rebel graveyard.”

The 1870 United States census listed (spelled as) Corinda Oliver, born about 1840 and living with a David Oliver, born about 1865 and the two were living in the household of Levi Roe in Jefferson County, Ohio. Nothing is known of the little girl however research has shown that the little boy was born about 1865 and his full name was David Martin Oliver and he died in 1943. According to the obituary of David Martin Oliver, on July 18th 1943 in the Pittsburg Sun Telegraph, he died at age seventy-eight and had been a life-long resident of Jefferson County, Ohio and had a father named Hiram Oliver who had been a Civil War veteran. John Wesley Hartup had no family or children.

The following article came from the newspaper The Ohio State Journal on May 3, 1866 on page three column three:

“CAMP CHASE IN ITS DECLINE- During the war there flourished as a thing of life, a few miles from Columbus, a great military center, a city within itself, a monstrous struggling thing, bound down by law and force, a something with an organism different from all around it, a power in the land looked to with anxious eye, a living giant preparing always for a great struggle. It is no longer a military center, no more a living thing; the city is deserted, the giant’s form, a skeleton. Hundreds and thousands of armed men, paraded on the guardians of the living thing; a single man, unarmed, keeps watch and ward over the remains of the thing dead waiting for burial. Two years ago you entered the precincts of Camp Chase armed with passes signed and countersigned; were directed by short spoken orderlies; warned by straight up and down sentinels; received with punctilious standoffishness by officials; and came away duly impressed with the military power of the country. Now you drive up to the gate as you would to that of a cemetery; the guardian presents himself in his shirt sleeves; you tell him your desires; he kicks away a huge stone; opens the gate; cautions you a little, and you enter unchallenged and unheralded to the mighty presence of the great solitude of loneliness. The rows of barracks remain unchanged; the flowers planted by some careful wife of some careless officer are ready to record that the hand of woman has been here; the flag staff stands without pulley, rope or flag; the chapel with its half change in the latter day to a theatre remains a monument of the one, a telltale of the other, the prison pens frown still with barred gates, but are silent within. In one, the scaffold upon which Hartup and Oliver were executed stands firm-the grim guardian of the ghostly solitude, and with beam in place, and trap half sprung, seems waiting for another victim. Everywhere are the marks of the skeleton. The pump stocks have all been withdrawn from the wells; the windows taken from the buildings grass growing on the parade ground. Old shoes tumble into promiscuous grouping, telling which buildings have been last occupied; and the martin-boxes give some signs of life. A little fruit tree, in the midst of all this loneliness, blossoms and puts forth leaves with all the proud defiance of nature, and with a scornful fling with every wave of wind, for the works of man perishing on every side. Camp Chase has but few visitors now, and these few can scarcely tell why they go. Proud and powerful while living, it is not great, but only silent and gloomy in its decline.”

Perhaps one day ground penetrating radar may be used on the Confederate dead at Camp Chase. And if so one of the graves may be that of Hiram Oliver and he should be the only one with a broken neck.

From Harper’s Weekly, Saturday, September 23, 1865